468x60

There are a lot of ways to earn money and get paid when you use Vinefire, so we'll go through the most common ways of earning and getting paid:

Read the "Terms and Condition to Learn more about this.

PayPal is the preferred option to send payouts to Vinefire members.

If PayPal doesn't conduct business in the country where you reside, or if you are unable to receive PayPal payments to the email address we have on record, we will contact you at said email address and request a physical address where we may send payment.

Get Vinefire Payments:

Vinefire is currently in "beta" mode and is not yet sending payments.

Your earnings will accumulate until we pay out.

468x60

There are a lot of ways to earn money and get paid when you use Vinefire, so we'll go through the most common ways of earning and getting paid:

Read the "Terms and Condition to Learn more about this.

PayPal is the preferred option to send payouts to Vinefire members.

If PayPal doesn't conduct business in the country where you reside, or if you are unable to receive PayPal payments to the email address we have on record, we will contact you at said email address and request a physical address where we may send payment.

Get Vinefire Payments:

Vinefire is currently in "beta" mode and is not yet sending payments.

Your earnings will accumulate until we pay out.

Wednesday, April 29, 2009

FOGHORNS AND RADIO SIGNALS

Ship captains can determine their position by identifying distinctive combinations of long and short horn blasts specific to each lighthouse. Some lighthouses are also equipped with radio beacons that transmit Morse-code radio signals.

These radio signals, which are distinguished by short (dot) and long (dash) combinations, have a range of up to 320 km (200 mi).

Lighthouse

Lighthouses are constructed at important points on a coastline, at entrances to harbors and estuaries, on rocky ledges or reefs, on islands, and even in the water. Lighthouses help identify a ship’s location, warn ships of potential hazards, and notify them that land is near.

Lighthouses differ from smaller beacons in that a lighthouse includes living quarters for a lighthouse keeper. Today, however, most lighthouses use automatic electric lights that do not require a full-time resident operator.

The first lighthouses were built long before the time of Christ. The earliest known reference to a lighthouse dates back to 1200 bc. This reference appeared in the Iliad, Homer’s Greek epic poem. The first onshore beacons that were used to guide ships were bonfires.

Eventually, bonfires were replaced with iron baskets filled with burning wood or coal and suspended on long poles. It was not until the 18th century that these baskets were replaced by oil or gas lanterns.

In the early to mid-20th century, electric beacons replaced oil and gas lanterns.

Tuesday, March 24, 2009

The Early Ships of the Explorers.

There was no such thing as an exploration model of ship. Captains, with their knowledge and experience had to acquire whatever they could get their hands on and find venture capitalists, people who would support and finance their journeys of exploration.

How well or richly the trip was backed by such mentors decided on how well the ship was prepared, often rebuild and rearmed, and how good ( and honest) the chandler was. Ships for exploration, not for style

Most ships for exploration were ex-trading ships re-fitted for the long journey. They were small, short and stubby for strength. Their bows lifted to on-coming waves and their high sterns prevented them being swamped from behind.

Many of them we only 70 - 100 metres in length. That's about 6 -9 sedan cars put end to end. Not a large home for a hundred or so men to live for 3 - 5 years sometimes.

While improvements in ship design had enabled the sailing ships of the 17th & 18th Centuries to travel much faster into the wind, the slower, smaller and 15th century boats were safer.

Wednesday, March 18, 2009

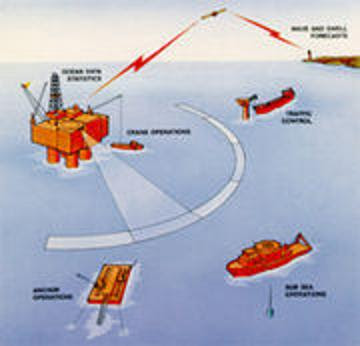

Wave radar

Wind waves can be measured by several radar remote sensing techniques. Several instruments based on a variety of different concepts and techniques are available to the user and these are all often called wave radars.

Instruments based on radar remote sensing techniques have become of particular interest in applications where it is important to avoid direct contact with the water surface and avoid structural interference.

A typical case is wave measurements from an offshore platform in deep waters with the presence of high currents making the mooring of a wave buoy enormously difficult. Another interesting case is a ship in transit where having instruments in the sea is highly impractical and interference from the ships hull must be avoided.

Marine navigation radars

Marine navigation radars (X band) provide sea clutter images which contain a pattern resembling a sea wave pattern. By digitizing the radar video signal it can be processed by a digital computer. Sea surface parameters may be calculated on the basis of these digitized images. The marine navigation radar operates in low grazing angle mode and wind generated surface ripple must be present. The marine navigation radar is non-coherent and is a typical example of an indirect wave sensor, because there is no direct relation between wave height and radar back-scatter modulation amplitude. An empirical method of wave spectrum scaling is normally employed. Marine navigation radar based wave sensors are excellent tools for wave direction measurements. A marine navigation radar may also be a tool for surface current measurements. Point measurements of the current vector as well as current maps up to a distance of a few km can be provided (Gangeskar, 2002). Miros WAVEX has its main area of application as directional wave measurements from moving ships.

Wednesday, March 11, 2009

Achelous class repair ship

As the US gained experience in amphibious operations, it was realized that some sort of mobile repair facility would be useful for repairing the damage that frequently occurred to smaller vessels such as LCVP's (Landing Craft Vehicle/Personnel). The Auxiliary Repair Light (ARL) ship was designed to meet this need, and the Achelous class was the only class to receive this designation.

In all, 39 Achelous class repair ships were built between 1943 and 1945.

China Ocean Shipping (Group) Company

According to the company, it owns over 130 vessels (with a capacity of 320,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU) and calls on over 100 ports worldwide.

Marine Insurance

Over time, marine insurance has become a mixture of broad property coverages, divided between land risks (inland marine) and sea risks (ocean marine).

Inland marine insurance covers domestic risks associated with some element of transportation. It has been broadened to include perils incidental to transportation of property and now deals mostly with personal and commercial property of a mobile nature. Its most familiar form is the personal articles “floater,” which offers an opportunity to insure many valuables, such as jewelry, furs, silverware, and fine arts, in a single policy.

Ocean marine insurance is broken into three basic types: hull (involving loss or damage to the ship); cargo (involving loss or damage to cargoes); and protection and indemnity (involving liability of shipowners to others).

Hull insurance affords protection to owners of all types of ships for loss or damage to their waterborne property. Typical perils insured against are stranding, sinking, fire, and collision. The hull policy offers an unusual coverage under its collision clause, which provides liability insurance for loss or damage to the other vessel involved in a collision, as well as to its cargo.

Cargo insurance is available for shippers of goods moving by sea or air in international trade. The terms of insurance can be specific (for example, loss or damage resulting from sinking or fire) or “all risk” and can be underwritten for a single transaction (special policy) or on an open-ended contract (open cargo policy) for the international trader. The open cargo policy is the most common form used and usually covers the cargo “warehouse to warehouse,” thus including exposure to those risks that are associated with land transportation as well.

When a ship is imperiled at sea because of fire, storm, or other danger, all efforts must be made to keep the ship afloat. Such efforts often cause damage to portions of the ship or cargo. To prevent inequity, each owner assumes a share of the property damaged or lost as a result of actions taken to save the ship.

This method of apportioning losses is known as general averaging.

Protection and indemnity (called P & I) insurance protects the vessel owners against their liability for damage to cargo in their care and custody; death or injury to passengers, crew, cargo loaders, and others; damage caused to piers, docks, underwater cables, and bridges; and, more recently, damage caused by pollution.

Other forms of related coverages are included in ocean marine insurance, such as miscellaneous liability policies for owners of piers, docks, marine repair facilities, marinas, and shipyards. Policies on yachts can be underwritten by an ocean marine insurer (usually for larger pleasure craft), providing property and liability insurance in one policy. Powerboats and smaller pleasure craft are more often insured by inland marine insurers. Builder's risk insurance is available to cover damage to a ship under construction.

Common exclusions found in marine insurance policies are loss or damage resulting from strikes, riots, civil commotions, and war. These risks can be, and frequently are, insured through use of endorsements for additional premiums.

Ocean marine insurance rates and policy forms are not regulated by any government authority. Coverage can be tailored to suit the individual needs of ship and cargo owners, and rates are based on the underwriter's experience and judgment in a competitive worldwide marketplace.

Underwriters consider many factors in setting terms and rates for a risk.

Factors common to all marine policies are the underwriter's experience with a commodity or vessel, the cargo owner's or shipowner's loss history, and current competition in the industry. Important factors relating to the ship include owner management, crew experience, trade routes, ports frequented, and age and maintenance of a vessel.

Marine and Other Forms of Transportation Insurance

Insurance for commercial ships or boats at sea, docked in a port, or on some inland waterways—as well as their cargo or passengers—is known as ocean marine insurance. There are four main types of ocean marine insurance:

(1) hull insurance

(2) cargo insurance

(3) freight insurance

(4) marine liability.

Hull insurance covers damage to a ship itself. Cargo insurance covers losses to a ship’s physical cargo. Freight insurance covers shippers against a loss of freight (payment for the transportation of cargo).

Marine liability covers damages to people and property from collisions and other incidents.

Businesses involved in transporting cargo or passengers by land or by air can purchase coverage similar to that of marine insurance. Insurance policies for commercial transport of cargo by land or air are commonly known as inland marine insurance. However, because of the increasing importance of the passenger airline industry, specialized property and casualty coverage, known as aviation insurance or aircraft insurance, has developed to cover aircraft and their cargo or passengers.

Thursday, February 19, 2009

Distances Between Post

Is a publication that lists the distances between major ports. Reciprocal distances between two ports may differ due to different routes chosen because of currents and climatic conditions. To reduce the number of listings needed, junction points along major routes are used to consolidate routes converging from different directions.

This book can be most effectively used for voyage planning in conjunction with the proper volume(s) of the Sailing Directions . It is corrected via the Notice to Mariners.

The positions listed for ports are central positions that most represent each port. The distances are between positions shown for each port and are generally over routes that afford the safest passage. Most of the distances represent the shortest navigable routes, but in some cases, longer routes, that take advantage of favorable currents, have been used. In other cases, increased distances result from routes selected to avoid ice or other dangers to navigation, or to follow required separation schemes

Passage planning or voyage planning

Is a procedure to develop a complete description of a vessel's voyage from start to finish. The plan includes leaving the dock and harbor area, the en route portion of a voyage, approaching the destination, and mooring. According to international law, a vessel's captain is legally responsible for passage planning, however on larger vessels, the task will be delegated to the ship's navigator.

Studies show that human error is a factor in 80 percent of navigational accidents and that in many cases the human making the error had access to information that could have prevented the accident.The practice of voyage planning has evolved from penciling lines on nautical charts to a process of risk management.

Sailing Directions

Is a 47-volume American navigation publication published by the Defense Mapping Agency Hydrographic/Topographic Center. Sailing Directions consists of 37 Enroute volumes and 10 Planning Guides. Planning Guides describe general features of ocean basins; Enroutes describe features of coastlines, ports, and harbors.

Sailing Directions are updated when new data requires extensive revision of an existing text. These data are obtained from several sources, including pilots and Sailing Directions from other countries.

One book comprises the Planning Guide and Enroute for Antartica . This consolidation allows for a more effective presentation of material on this unique area.

The Planning Guides are relatively permanent; by contrast, Sailing Directions (Enroute) are frequently updated. Between updates, both are corrected by the Notice to mariners.

Notice to Mariners

advises mariners of important matters affecting navigational safety, including new hydrographic information, changes in channels and aids to navigation, and other important data.

One example is the American publication made available weekly by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency NGA, prepared jointly with the National Ocean Service (NOS) and the U.S Coastguard. The information in the Notice to Mariners is formatted to simplify the correction of paper charts,Sailing Directions, LightsList, and other publications produced by DMAHTC, NOS, and the U.S. Coast Guard.

Celestial Navigation,

A position fixing technique that was devised to help sailors cross the featureless oceans without having to rely on dead reckoning to enable them to strike land. Celestial navigation uses angular measurements (sights) between the horizon and a common celestial object. The Sun is most often measured. Skilled navigators can use the Moon, Planets or one of 57 navigational stars whose coordinates are tabulated in nautical almanacs.

1.Position fixing

Is the branch of navigation concerned with the use of a variety of visual and electronic methods to determine the position of a ship, aircraft or person on the surface of the Earth.

2. Dead reckoning (DR)

Is the process of estimating one's current position based upon a previously determined position, or fix, and advancing that position based upon known speed, elapsed time, and course. While traditional methods of dead reckoning are no longer considered primary in most applications, modern inertial navigationsystem, which also depend upon dead reckoning, are very widely used.

3. The navigational stars

Are used in celestial navigation because they are some of the brightest celestial objects due to their high luminosities and/or their proximity to our solar system. Most of these stars are a subset of the list of brightest stars and are defined by convention and nautical tradition.

4. A nautical almanac

Is a publication describing the positions and movements of celestial bodies for the purpose of enabling navigators to use celestial navigation to determine the position of their ship while at sea including the sun, moon, planets, and 57 stars chosen for their ease of identification and wide spacing. The Almanac specifies for each whole hour of the year the position on the Earth's surface at which each body is directly overhead. The Sun, Moon and Planets 'move' independently and so are specified separately, but for the stars only Aries is specified, the other stars having a set angular distance from that. The navigator can use difference tables to extrapolate the position of each object for each minute of time.

Car Perry

Major Shipping Trade route

This map shows shipping routes from the perspective of the north pole, which falls roughly at the map’s center. Called a polar-azimuthal map, it was created by flattening the globe from the top, which provides a better understanding of the way the routes curve around the planet. Although there are hundreds of potential shipping paths across the world’s oceans, almost all ships travel on a few well-established routes. Determined by geography, economics, and historical tradition, the routes serve to connect major industrial regions to one another and to areas that produce raw materials.

Cargo Ship

A large cargo ship is unloaded at the Brooklyn pier in New York. Both containers and wooden crates protect the shipped goods from destruction and vandalism.

Container Ship

Container ship Arlberg is shown here as it leaves New York Harbor. The ship is part of an intermodal system in which locked and sealed containers are carried on ships, trucks, trains, and airplanes. Container shipping reduces transport costs by decreasing loading costs and reducing pilferage losses. Various labor groups have historically opposed development of container shipping, fearing that the increased automation would lead to lost jobs.

Oil Tanker

As their name suggests, tankers are mammoth floating tanks that transport liquid cargo such as petroleum and natural gas. A tanker has several individual compartments inside the main body, allowing it to carry thousands of tons of petroleum. Unfortunately, few tankers are designed with double or reinforced hulls, so that when accidents occur at sea, devastating amounts of oil may be spilled.

Flag of Convenience

In 1995, 75 million gross metric tons of shipping was registered in Panama, making it the world's largest merchant fleet. Ships registered under flags of convenience accounted for 34 percent of the world's fleet in 1993.

History

Advances in the 19th Century

Until the 19th century, ships were owned by the merchant or by the trading company; common-carrier service did not exist.

On January 5, 1818, the full-rigged American ship James Monroe, of the Black Ball Line, sailed from New York City for Liverpool, inaugurating common-carrier line service on a dependable schedule. A policy of sailing regularly and accepting cargo in less-than-shipload lots enabled the Black Ball Line to revolutionize shipping.

Two technological developments furthered progress toward present-day shipping practices: the use of steam propulsion and the use of iron in shipbuilding. In 1819 the American sailing ship Savannah crossed the Atlantic under steam propulsion for part of the voyage, pioneering the way for the British ship Sirius, which crossed the Atlantic entirely under steam in 1838. Iron was first used in the sailing vessel Ironsides, which was launched in Liverpool in 1838.

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 was of great economic importance to shipping. Coinciding with the perfection of the triple-expansion reciprocating engine, which was both dependable and economical in comparison with the machinery of the pioneer vessels, the completion of the canal made possible rapid service between western Europe and Asia. The first steam-propelled ship designed as an oceangoing tanker was the Glückauf, built in Britain in 1886. It had 3,020 deadweight tons (dwt; the weight of a ship's cargo, stores, fuel, passengers, and crew when the ship is fully loaded) and a speed of 11 knots.

The 20th Century

Among the technological advances at the turn of the century was the development by the British inventor Charles A. Parsons of the compound steam turbine, adapted to maritime use in 1897. In 1903 the Wandal, a steamer on the Volga River, was powered by the first diesel engine used for ship propulsion. The Danish vessel Selandia was commissioned as the first seagoing motor ship in 1912.

After World War I significant progress was made especially in the perfection of the turboelectric drive. During World War II, welding in ship construction supplanted the use of rivets.

The keel of the first nuclear-powered passenger-cargo ship, the Savannah, was laid in Camden, New Jersey, on May 22, 1958, and the ship was launched in 1960. In 1962 it was chartered to a private company for experimental commercial use, but it did not prove financially successful.

Nature of Shipping Industry

Trade Routes

Most of the world's shipping travels a relatively small number of major ocean routes: the North Atlantic, between Europe and eastern North America; the Mediterranean-Asian route via the Suez Canal; the Panama Canal route connecting Europe and the eastern American coasts with the western American coasts and Asia; the South African route linking Europe and America with Africa; the South American route from Europe and North America to South America; the North Pacific route linking western America with Japan and China; and the South Pacific route from western America to Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia, and southern Asia. The old Cape of Good Hope route pioneered by Vasco da Gama and shortened by the Suez Canal has returned to use for giant oil tankers plying between the Persian Gulf and Europe and America. Many shorter routes, including coastal routes, are heavily traveled.

Coastwise Shipping

Technically, coastal shipping is conducted within 32 km (within 20 mi) of the shoreline, but in practice ship lanes often extend beyond that distance, for reasons of economy and safety of operation. In the U.S., coastal shipping is conducted along the Pacific, Atlantic, and Gulf coasts. Under the restriction known as cabotage, the U.S. and many other nations permit only vessels registered under the national flag to engage in coastal trade. Among many small European countries cabotage does not apply, and short international voyages are common. A special feature of coastal shipping in the U.S. is the trade between the Pacific coast and the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Vessels engaged in this trade traverse the open sea and utilize the Panama Canal; however, they are covered by cabotage laws. In coastal and short-distance shipping, special-purpose ships are often employed, such as car ferries and train ferries.

Inland Waterways

A major part of all the world's shipping moves on inland waterways—rivers, canals, and lakes. Usually such shipping employs smaller, lighter vessels, although in some cases oceangoing ships navigate inland waterways, for example, the St. Lawrence Seaway route to the Great Lakes of North America. Containerization, lighter-aboard-ship, and barge-aboard-ship operations have facilitated the shipping of cargoes between oceangoing vessels and those of the inland waterways.

Liner Service

Liner service consists of regularly scheduled shipping operations on fixed routes. Cargoes are accepted under a bill-of-lading contract issued by the ship operator to the shipper.

Competition in liner service is regulated generally by agreements, known as conferences, among the shipowners. These conferences stabilize conditions of competition and set passenger fares or freight rates for all members of the conferences. In the U.S., steamship conferences are supervised by the Federal Maritime Commission in accordance with the Shipping Act of 1916. Rate changes, modifications of agreements, and other joint activities must be approved by the commission before they are effective. Measures designed to eliminate or prevent competition are prohibited by law.

Tramp Shipping

Tramps, known also as general-service ships, maintain neither regular routes nor regular service. Usually tramps carry shipload lots of the same commodity for a single shipper. Such cargoes generally consist of bulk raw or low-value material, such as grain, ore, or coal, for which inexpensive transportation is required. About 30 percent of U.S. foreign commerce is carried in tramps.

Tramps are classified on the basis of employment rather than of ship design. The typical tramp operates under a charter party, that is, a contract for the use of the vessel.

The center of the chartering business is the Baltic Exchange in London, where brokers representing shippers meet with shipowners or their representatives to arrange the agreements. Freight rates fluctuate according to supply and demand: When cargoes are fewer than ships, rates are low. Charter rates are also affected by various other circumstances, such as crop failures and political crises.

Charter parties are of three kinds, namely, the voyage charter, the time charter, and the bareboat charter. The voyage charter, the most common of the three, provides transport for a single voyage, and designated cargo between two ports in consideration of an agreed fee. The charterer provides all loading and discharging berths and port agents to handle the ship, and the shipowner is responsible for providing the crew, operating the ship, and assuming all costs in connection with the voyage, unless an agreement is made to the contrary. The time charter provides for lease of the ship and crew for an agreed period of time. The time charter does not specify the cargo to be carried but places the ship at the disposal of the charterer, who must assume the cost of fuel and port fees. The bareboat charter provides for the lease of the ship to a charterer who has the operating organization for complete management of the ship. The bareboat charter transfers the ship, in all but legal title, to the charterer, who provides the crew and becomes responsible for all aspects of its operation.

The leading tramp-owning and tramp-operating nations of the world are Norway, Britain, the Netherlands, and Greece. The carrying capacity of a typical, modern, well-designed tramp ship is about 12,000 dwt, and its speed is about 15 knots. The recent trend is toward tramps of 30,000 dwt, without much increase in speed.

Industrial Carriers

Industrial carriers are vessels operated by large corporations to provide transportation essential to the processes of manufacture and distribution. These vessels are run to ports and on schedules determined by the specific needs of the owners. The ships may belong to the corporations or may be chartered. For example, the Bethlehem Steel Corp. maintains a fleet of Great Lakes ore carriers, a number of specialized ships that haul ore from South America to Baltimore, Maryland, and a fleet of dry-cargo ships that transports steel products from Baltimore to the Pacific coast. Many oil companies maintain large fleets of deep-sea tankers, towboats, and river barges to carry petroleum to and from refineries.

Tanker Operation

All tankers are private or contract carriers. In the 1970s some 34 percent of the world tanker fleet, which aggregates about 200 million dwt, was owned by oil companies; the remaining tonnage belonged to independent shipowners who chartered their vessels to the oil companies. So-called supertankers, which exceed 100,000 dwt, are employed to transport crude petroleum from the oil fields to refineries. The refined products, such as gasoline, kerosene, and lubricating oils, are distributed by smaller tankers, generally less than 30,000 dwt, and by barges.

Vessel Types

Cargo Ships

Cargo ships carry packaged goods, unitized cargo (cargo in which a number of items are consolidated into one large shipping unit for easier handling), and limited amounts of grain, ore, and liquids such as latex and edible oils. A few passengers are accepted on some cargo liners. Specialized ships are designed and built to carry certain types of cargo, for example, automobiles or grain.

Container Ships

In the late 1950s container ships set the pattern for technological change in cargo handling and linked the trucking industry to deep-Sea shipping. These highly specialized ships carry large truck bodies and can discharge and load in one day, in contrast to the ten days required by conventional ships of the same size. The rapid development of the container ship began in 1956, when Sea-Land Service commenced operations between New York City and Houston, Texas. Barge-aboard, or lighter-aboard, ships, also called seabees (sea barges) or LASH (lighter-aboard ships), resulted from an evolutionary development of the container ship. They are capable of carrying about 38 barges, or up to 1,600 containers, or a combination of containers and barges. Their design enables them to deliver cargo to developed or undeveloped ports, without the need for berthing.

Tankers

Tankers, designed specifically to carry liquid cargoes, usually petroleum, have grown to many-compartmented giants of a million metric tons and more. Despite their great size, their construction is simple, as is, for the most part, their operation. A major problem with the giant tankers is the severe environmental damage of oil spills, resulting from collision, storm damage, or leakage from other causes.

Specialized tankers transport liquefied natural gas (LNG), liquid chemicals, wine, molasses, and refrigerated products.

Treaties and Conventions

Many treaties and conventions have been adopted over the years with the objective of increasing the safety of life at sea. One of the most important agreements provided for the establishment of the International Iceberg Patrol in 1913, after the Titanic disaster. Under the International Load-Line Convention of 1930, ship loading was regulated on the basis of size, cargo, and route of the vessel. The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, which governs ship construction, was ratified by most maritime nations in 1936, and updated in 1948, and again in 1960 and 1974.

Shipping

Shipping Industry, the industry devoted to moving goods or passengers by water. Passenger operations have been a major component of shipping, but air travel has seriously limited this aspect of the industry. The enormous increase, however, in certain kinds of cargo, for example, petroleum, has more than made up for the loss of passenger traffic. Although raw materials such as mineral ores, coal, lumber, grain, and other foodstuffs supply a vast and still growing volume of cargo, the transportation of manufactured goods has increased rapidly since World War II.